By Vincent Michael Valvo

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

For the better part of the 20th century, the Fuller Brush Man was a ubiquitous American icon, seemingly getting his foot in the door of every household in America.

Founded in 1906 in Boston, the Fuller Brush Company rose to prominence in Hartford (and later East Hartford) after moving there in 1909. By mid-century, the suitcase-toting Fuller salesman, knocking on the doors of rural farmers and urban housewives, became such a part of the national culture that Hollywood was compelled to make two movies about him: The Fuller Brush Man starring Red Skelton in 1948, and its sequel, The Fuller Brush Girl, starring Lucille Ball in 1950. Walt Disney cast Donald Duck as a Fuller Brush Man in one cartoon. And in Disney’s 1933 The Three Little Pigs, the Big Bad Wolf was modeled after a Fuller Brush Man. After all, who else had a reputation for being able to get into a house when no one else could?

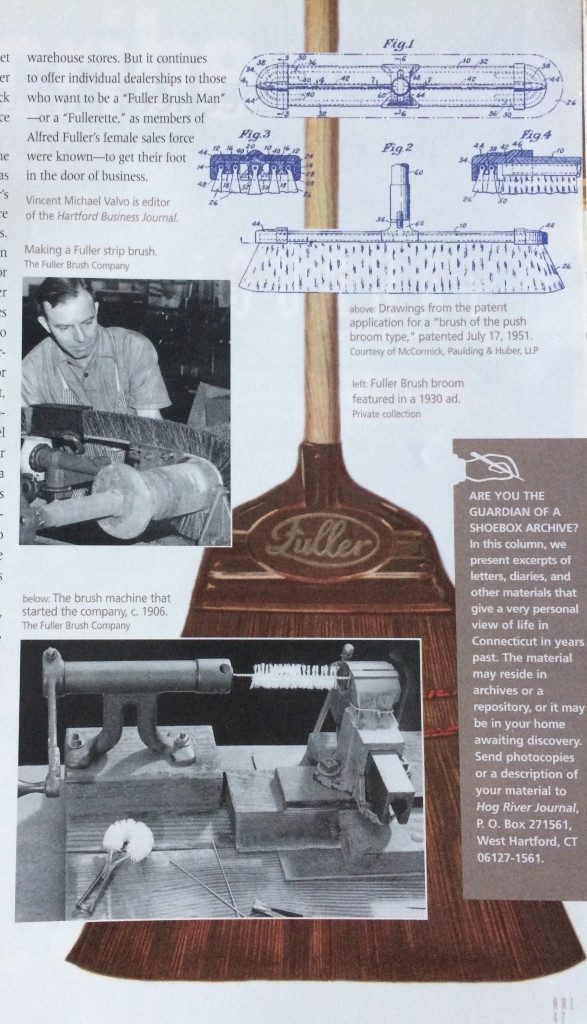

The rise of the Fuller Brush Company is a story of invention, perseverance, and hard work. Connecticut is fortunate to have, in the private archives of the intellectual property law firm McCormick, Paulding and Huber, the company’s original patent records. These records, with their attendant diagrams, offer insight into the workings of a distinctly American entrepreneurial enterprise.

In 1906, Alfred C. Fuller set up a small shop in his sister’s house in Somerville, Massachusetts, just outside of Boston. He had spent three years as a door-to-door salesman, often getting turned away by prospects because the merchandise he peddled was so shoddy. He realized that selling inferior products was not a path to success. So he chose one of the most common of those products and set out to make it better.

It’s hard to imagine today how important good quality brushes were to the average household during the 20 th century. Brushes were used for cleaning stairs, shining radiators, bathing babies, restoring silk hats, emptying spittoons, and scrubbing milk bottles. With no vacuum cleaners and only rudimentary washing machines, they were the workhorses of housework. But most brushes were also made by hand, often poorly, and their ill-conceived designs prevented their doing the work for which they were intended. Fuller meticulously set about to change that. He interviewed potential customers—mostly women—and with a $375 investment created a brush-making machine that could produce a product with more bristles and in various contours designed for specific tasks. Then he set about selling them the way he knew best: by going door-to-door.

It’s hard to imagine today how important good quality brushes were to the average household during the 20 th century. Brushes were used for cleaning stairs, shining radiators, bathing babies, restoring silk hats, emptying spittoons, and scrubbing milk bottles. With no vacuum cleaners and only rudimentary washing machines, they were the workhorses of housework. But most brushes were also made by hand, often poorly, and their ill-conceived designs prevented their doing the work for which they were intended. Fuller meticulously set about to change that. He interviewed potential customers—mostly women—and with a $375 investment created a brush-making machine that could produce a product with more bristles and in various contours designed for specific tasks. Then he set about selling them the way he knew best: by going door-to-door.

In his first year, he made the remarkable sum of $8,500, proof that there was a market for his products. That’s when Fuller moved to Hartford—a city he had visited on his sales trips—to open full-scale manufacturing operations. Writing about Fuller on the company’s 80 th anniversary, Gerald Carson noted in American Heritage magazine that “Fuller moved to Hartford, Connecticut, a city with both spiritual and material attractions for him. Fuller’s first wire-twisting machine had been built at Hartford; the great Fuller family Bible that reposed on the center table in the Fuller parlor back home … had been printed in Hartford, which made it for the virtuous youth a heavenly city built upon a hill; and he had noticed on an earlier visit that the insurance capital had long avenues of big, old Victorian residences, filled with dust-catching grillwork, wood paneling, dadoes, moldings, stair banisters, steam radiators, and spacious but unsanitary kitchens—all in urgent need of the elemental tools of cleanliness. Prosperous but dusty Hartford was a brush man’s dream.”

But he realized he needed help. Fuller served as inventor, machine operator, and chief salesman. In 1909, he wrote to the New York-based, nationally distributed Everybody’s Magazine and placed a four-line advertisement seeking door-to-door salesmen. The response was overwhelming, and in short order Fuller had a network of nearly 300 dealers across the nation.

And with his factory (originally called the Capital Brush Co., but changed to the Fuller Brush Company by 1910) flourishing, Fuller’s sales force became an instantly recognizable, familiar element in the American landscape—even more so when the Saturday Evening Post coined “The Fuller Brush Man” sobriquet in 1922. His company operated on three basic principles: Make it work, make it last, and guarantee it no matter what.

“My wife used to love seeing the Fuller Brush Man come to the house,” said Theodore Paulding. Mary Rose Paulding used to look forward to the knock on the door of her Wethersfield home, he said. “Their products were higher priced, but they were better products than you could get elsewhere.”

Paulding knew that better than most. As a name partner at McCormick, Paulding & Huber in Hartford, he was the attorney who handled patent applications for the Fuller Brush Company.

While fame came to Fuller’s cadre of commissioned salespeople, it was the men behind the Fuller Brush Man who made the company the success that it was. Fuller had an entire research division, employing dozens of inventors, hard at work in Hartford, and in East Hartford after the company moved there in 1960. Fuller’s “engineering department” constantly tried to improve the company’s products. Patent applications for better carpet sweepers, better floor brushes, better brooms still take up volumes at McCormick Paulding’s offices in Hartford’s CityPlace building today.

But Fuller didn’t limit his tinkering to the products themselves. “What impressed me was the machine patents,” recalls Paulding. Fuller’s Hartford and East Hartford operations were highly automated for their time, he notes. Fuller’s engineers filed dozens of patents on brush-making machinery and machines for other products, too, as the manufacturer expanded into other lines of goods. Besides consumer-oriented products, the company also made industrial products such as large motor-driven brushes used in developing images for newspaper printing plates. At one point, Fuller’s engineers were working on an automobile exhaust muffler using a stainless steel helix-shaped brush, said Dick Bolt, a former Fuller inventor. One of the ideas was to build a muffler with the coiled brush so car owners could pull it out—a combustion-altering technique to make the vehicle louder and faster, so they could go racing on weekends. It was one of the few Fuller products that didn’t find its way to market.

“This was complex machinery, very high-end stuff,” said Paulding. To achieve the quality products he wanted to sell, Fuller needed a quality manufacturing facility. And the only way to get that was to invent it, one machine at a time. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office lists more than 300 patents held in the Fuller Brush Company’s name.

Alfred Fuller died in 1973. His firm had already passed him by, being acquired by the Sara Lee Corporation in 1968. At the time, the Fuller Brush Company was using an early Honeywell 200 computer to monitor the workings of 22,000 dealers across the world. Today, Fuller is owned by an investment group and calls Great Bend, Kansas, its home. It sells most of its products via catalog or through warehouse stores. But it continues to offer individual dealerships to those who want to be a “Fuller Brush Man”—or a “Fullerette,” as members of Alfred Fuller’s female sales were known—to get their foot in the door of business.