By Leah S. Glaser

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The summer of 2020 brought a national reckoning over our collective memory as embodied in public statues, while superstorms and wildfires exacerbated by climate change also consumed our collective memory in the form of old-growth trees and forests. Rich in environmental benefits, mature trees have also defined Connecticut’s landscape and self-identity. They tie local histories to place by physically and symbolically storing individual and collective memory.

Exhibit A is Connecticut’s Charter Oak. Forests supplied Eastern Woodland tribes with tools, shelter, and food as they seasonally migrated to and from the shoreline. A lone tree is a central element of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Seal and represents their forested homelands. In Hartford, descendants of white settlers appropriated an oak, known to local Native people (likely the Saukiog) as a “peace tree,” for Connecticut’s own creation story about the Charter Oak. After a storm destroyed the massive and ancient tree in 1856, it earned its own memorial obelisk erected in Hartford by the Connecticut Society of Colonial Wars in 1907.

Few places are more historically and culturally tied to the shade tree than state forests and local parks. These landscapes reflect deliberate decisions by administrators and activists in the early 20th century to save parts of our historic landscape in response to rapid industrial development. Connecticut led national forestry policy. It was among the first to hire a state forester and to purchase forests to protect state watersheds and timber supplies. [See “Connecticut’s Park and Forest Pioneers,” Winter 2016/2017.]

During the Progressive Era, groups advocated for tree conservation on environmental grounds. Other groups believed in preserving trees as an extension of New England’s heritage and sponsored tree plantings for almost any anniversary occasion. In 1934 Katharine Matthies, a member of the Connecticut Daughters of the American Revolution, published Trees of Note in Connecticut (Yale University Press). In it she listed trees for their size and beauty and a few for their historical significance, such as scions of Charter Oak planted across the state.

“Witness trees” connect past and present, often inscribing the landscape with colonial land claims and thus asserting the disputable narrative that Native people willingly surrendered fertile land to European settlers. Matthies noted a sycamore that marked an Indian planting ground known as Hequetch that first was protected by treaty and then reportedly was deeded to settlers in Stamford. Other trees, Matthies noted, marked colonial victories over the British Empire. A sycamore in Danbury “witnessed the retreat of the British to Ridgefield after they burned Danbury.” Sadly, this tree was cut down in 2014. A tamarak tree in Ridgefield marked the site where 500 patriots under the command of Benedict Arnold built a barricade to British troops. The former president and conservationist Theodore Roosevelt planted the “Roosevelt Oak” in East Haven on Arbor Day, March 9, 1908 to mark General Lafayette’s encampment there during the Revolutionary War.

Since 1985 the Connecticut College Arboretum Notable Trees Project has maintained digital records of thousands of individual trees across the state, recording their size, location, ownership, and condition. Yet this database only suggests the potential for trees to serve as living, historic touchstones that can mark, locate, and recall events that help connect people to place and to the past. I would argue that older trees and old-growth forests rival stone monuments in historic significance. They can yield new information about changes to landscapes through dendrochronology. But they also reflect the ways communities remember their history. By reflecting ideas about natural resources as living and evolving vessels of communal memory, trees can serve as some of the most significant monuments to our past.

Leah Glaser is professor of American history and coordinator of the Public History Program at Central Connecticut State University. She is co-editing the forthcoming book Branching Out: The Public History of Trees. She was guest editor of the Winter 2016/2017 issue, “Connecticans in the American West.”

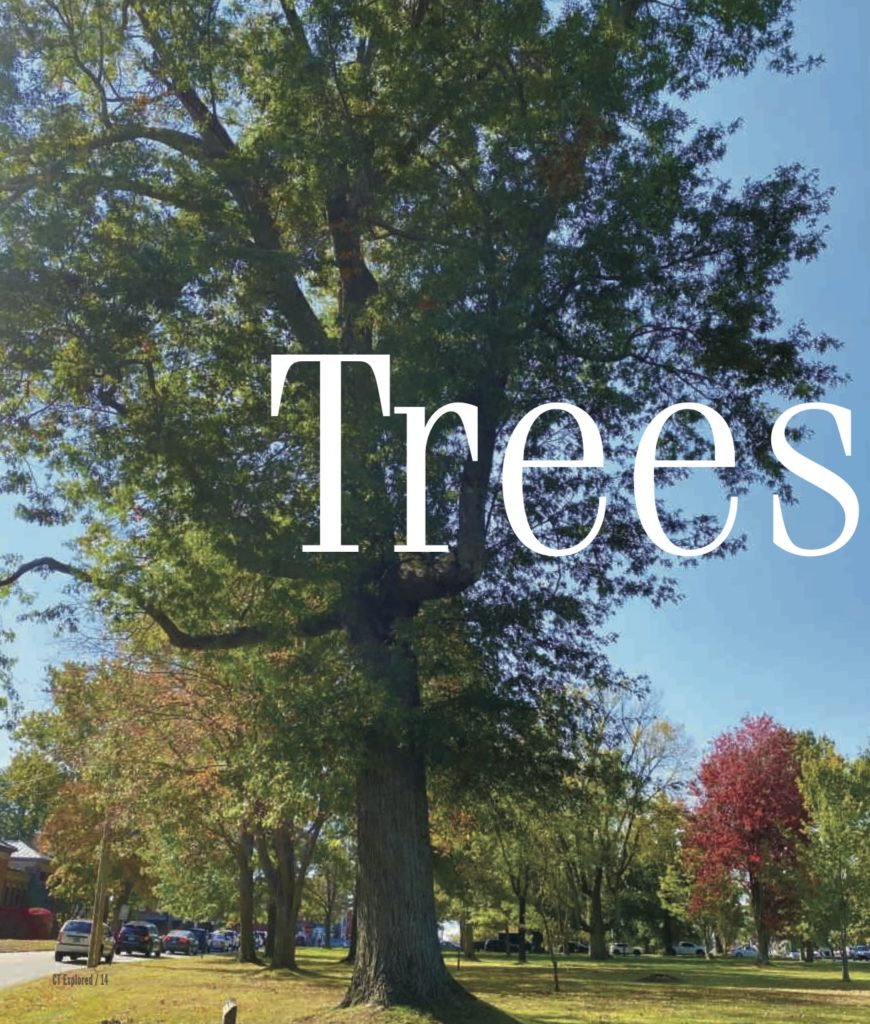

top of page: “Connecticut Constitution Oak,” Litchfield. photo: Mary M. Donohue

Katharine Matthies, in Trees of Note in Connecticut, describes a custom practiced just after the American Revolution in which people planted sets of trees for each of the colonies. Governor Oliver Wolcott, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, planted 13 sycamores in his hometown of Litchfield. People in the West Division of Hartford (now West Hartford) planted 13 elms in 1777 to commemorate the American victory at Saratoga Springs. In 1876 residents of Old Saybrook and other Connecticut towns planted Centennial Elms, five of which survive. In 1902 Connecticut held a convention in Hartford to consider updating the state constitution. To commemorate the occasion, Joseph R. Hawley, one of Connecticut’s U.S. senators, arranged for the U.S. Department of Agriculture to provide Pin Oak seedlings, which he distributed to each of the 168 town delegates at the close of the convention. The delegates planted the seedlings on town greens, in school yards and churchyards and, in many cases, on the delegate’s own property. The measure to revise the constitution had failed, but many of the trees still survive.

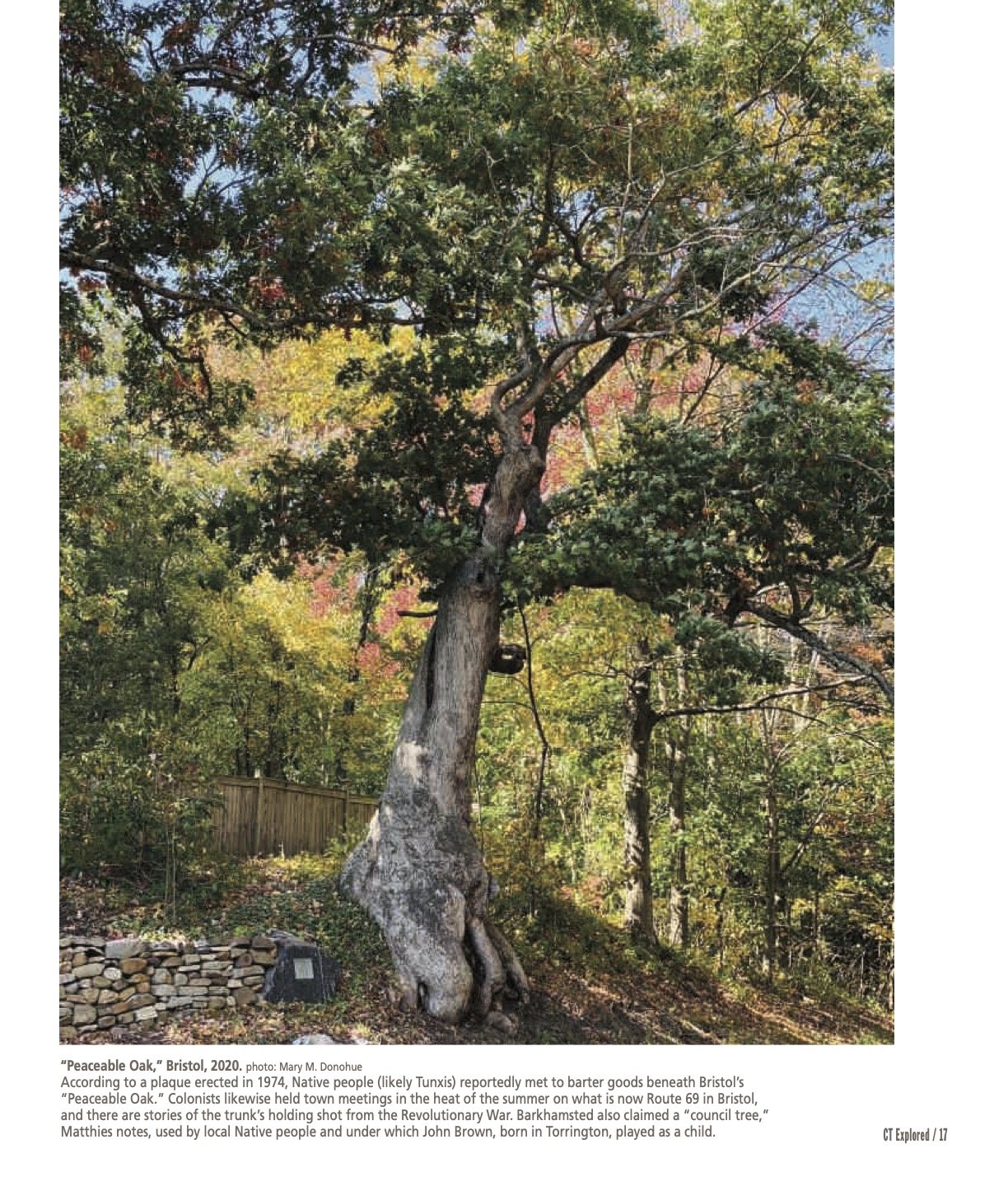

top: Scion of the Charter Oak, Bushnell Park, Hartford, 2020. photo: Mary M. Donohue

Charter Oak scions have also earned commemorative significance as descendants of the state’s “first tree.” They carry the idea of political independence and liberty. Some still stand in places like New Britain’s Fairview Cemetery and Hartford’s Bushnell Park.

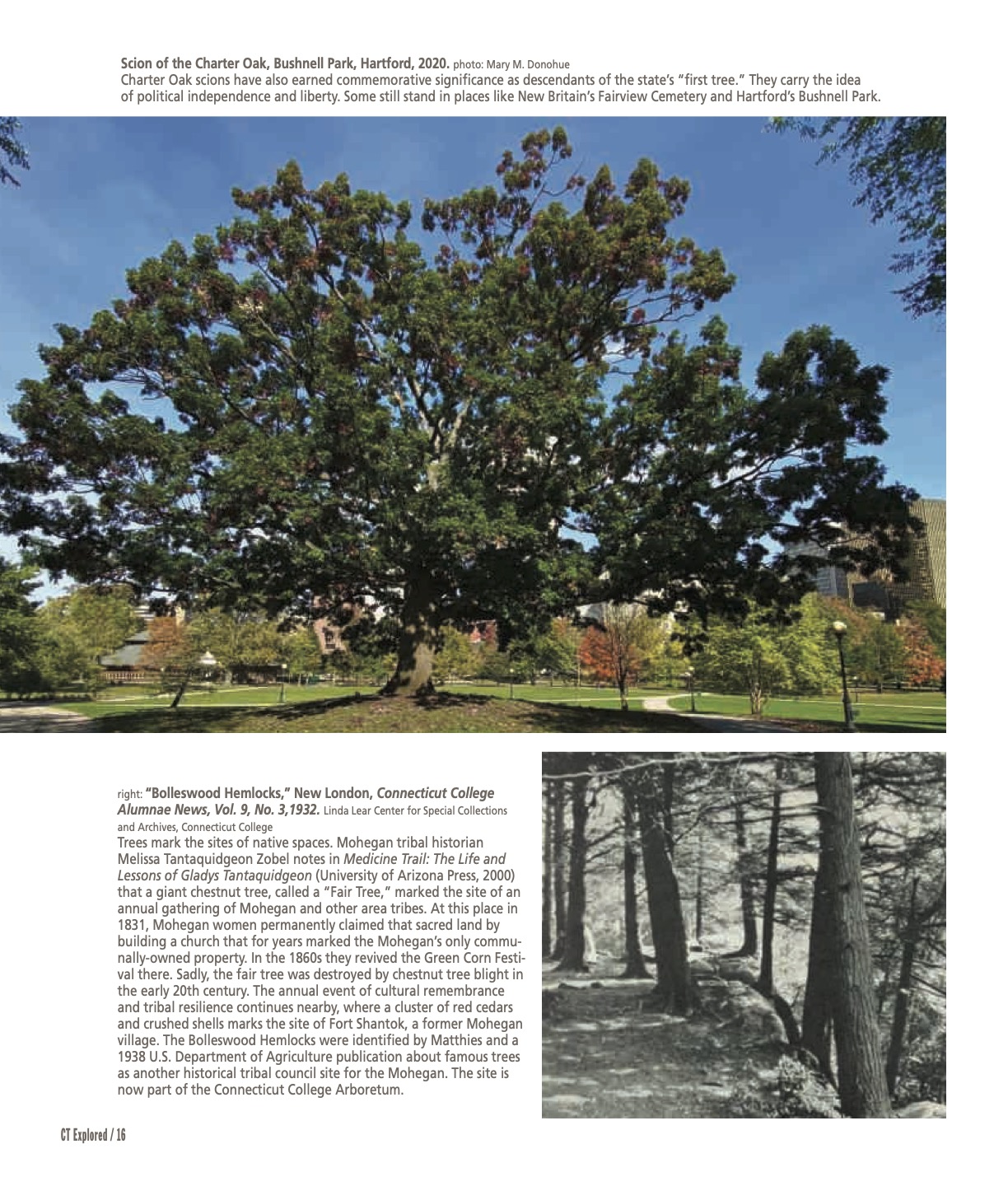

below: “Bolleswood Hemlocks,” New London, Connecticut College Alumnae News, Vol. 9, No. 3,1932. Linda Lear Center for Special Collections and Archives, Connecticut College

Trees mark the sites of native spaces. Mohegan tribal historian Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel notes in Medicine Trail: The Life and Lessons of Gladys Tantaquidgeon (University of Arizona Press, 2000) that a giant chestnut tree, called a “Fair Tree,” marked the site of an annual gathering of Mohegan and other area tribes. At this place in 1831, Mohegan women permanently claimed that sacred land by building a church that for years marked the Mohegan’s only communally-owned property. In the 1860s they revived the Green Corn Festival there. Sadly, the fair tree was destroyed by chestnut tree blight in the early 20th century. The annual event of cultural remembrance and tribal resilience continues nearby, where a cluster of red cedars and crushed shells marks the site of Fort Shantok, a former Mohegan village. The Bolleswood Hemlocks were identified by Matthies and a 1938 U.S. Department of Agriculture publication about famous trees as another historical tribal council site for the Mohegan. It is now part of the Connecticut College Arboretum.

“Peaceable Oak,” Bristol, 2020. photo: Mary M. Donohue

According to a plaque erected in 1974, Native people (likely Tunxis) reportedly met to barter goods beneath Bristol’s “Peaceable Oak.” Colonists likewise held town meetings in the heat of the summer on Route 69 in Bristol, and there are stories of the trunk’s holding shot from the Revolutionary War. Barkhamsted also claimed a “council tree,” Matthies notes, used by local Native people and under which John Brown, born in Torrington, played as a child.

“Pinchot Sycamore,” Simsbury. photo: Leah S. Glaser

The state’s largest tree, the Pinchot Sycamore along the Farmington River in Simsbury, is almost 28 feet in girth and 104 feet tall. In 1965 it was dedicated to town native Gifford Pinchot, co-founder of the forestry school at Yale University (the nation’s oldest) and first chief of the U.S. Forest Service. Not far distant, the spidery-limbed Granby Oak, with thick branches that both stretch to the sky and dip toward the ground, is thought by many to be the state’s most picturesque tree, despite sustaining storm damage in recent years. Since 1975 its profile has been emblazoned on the Granby town seal.

inset, left: “Whipping Post Elm,” Litchfield, 1901. Litchfield Historical Society. inset right: “Witch Elm,” Hartford, 1934, from Trees of Note of Connecticut.

While several witness trees noted in Matthies’s book marked sites of colonial justification, others hold painful memories and serve as both symbols of terror and memorials to victims of oppression. Until 1815 Litchfield residents used the elm in front of the county jail as a whipping post, since it was small enough for arms to stretch around it with hands tied together. The “Witch Elm,” which reportedly was used to hang Connecticut’s last convicted “witch,” stood on Albany Avenue in Hartford until 1930.

GO TO NEXT STORY

Explore!

Read all of our stories about Landscape & the Environment on our TOPICS page.

LISTEN! Grating the Nutmeg 121: Rooted in History—Connecticut’s Trees

Listen to Leah Glaser’s students’ tales of 15 witness trees in Connecticut.

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

Sign up for our free bi-weekly e-newsletter